HOW THE PHILADELPHIA CENTER FOR GUN VIOLENCE REPORTING IS INTERRUPTING AMERICA’S NARRATIVE ON GUN VIOLENCE

HOW THE PHILADELPHIA CENTER FOR GUN VIOLENCE REPORTING IS INTERRUPTING AMERICA’S NARRATIVE ON GUN VIOLENCE

Welcome to PCGVR, the place where ethical, empathetic, and impactful gun violence reporting begins. Our work is driven by a vast array of life experiences—some sad, some maddening, some hopeful, some inspiring. But if we had to pick one place to start, it would be with our founder, Jim MacMillan.

Jim began his photojournalism career in Boston, working in various capacities for the Associated Press, the Boston Herald and The Boston Globe. Until finally, he found his way down the East Coast to the Philadelphia Daily News, where he would spend the better part of two decades documenting spot news.

In many cities, ‘spot news’ means a lot of fires, collisions, and weather stories.

In Philadelphia, it meant gun violence. A lot of gun violence.

One day, life changed.

After many years in photography, Jim found himself back at school, examining the intersection of journalism and trauma, both as a student and as a teacher. Then, quite serendipitously, after asking a guest speaker from one of his classes if there was anything he could do to return the favor, Jim was, as he puts it, “corralled” into violence prevention work.

Four years later, Jim was awarded a residential fellowship at the Reynolds Journalism Institute at the University of Missouri School of Journalism. His goals? To convene a national conference on better gun violence reporting, publish a preliminary set of best practices, and launch an enduring organization to carry the work forward (you can guess what organization that would be).

Meanwhile, at a hospital across town, a trauma surgeon was trying to understand why she was seeing so many patients with gunshot wounds in her new home of Philadelphia.

Dr. Jessica Beard turned to the local evening news for help.

She started thinking about how she could work with journalists to make the root causes of gun violence and research-backed solutions to gun violence part of the narrative.

Then, some magic happened.

The summit.

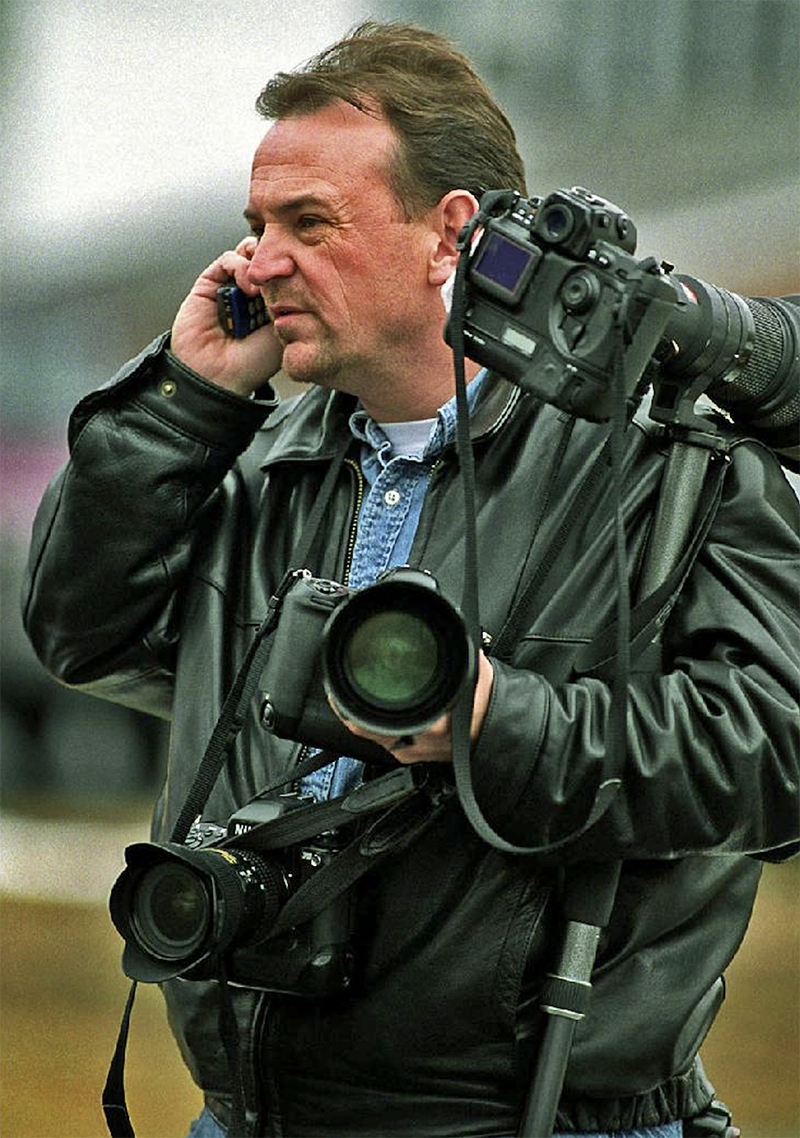

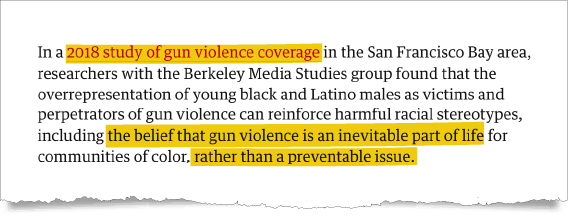

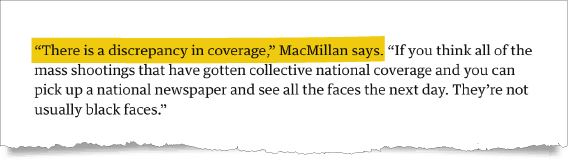

Those who have experienced the devastating impacts of gun violence have long known how harmful the media can be for victims and survivors. But in 2019, the idea that how journalists report on gun violence may actually be causing harm was just beginning to percolate in Philadelphia, thanks in large part to that op-ed from Jim and Jessica.

It was time for Jim to tackle his first big fellowship goal:

The Better Gun Violence Reporting Summit, held at WHYY Public Media in Philadelphia.

…including several people who would go on to play important roles in PCGVR’s future. Let’s meet a few of them.

Now remember, back in 2019 when The Better Gun Violence Reporting Summit was held, PCGVR technically did not yet exist. It was just Jim and his fellowship. But that Summit would shape the future of the organization.

Summit participants were energized. But their problems weren’t solved yet.

Abené called Jim for an interview.

Dr. Jessica Beard was awarded her fellowship, thanks to the Stoneleigh Foundation. And The Philadelphia Center for Gun Violence Reporting took off.

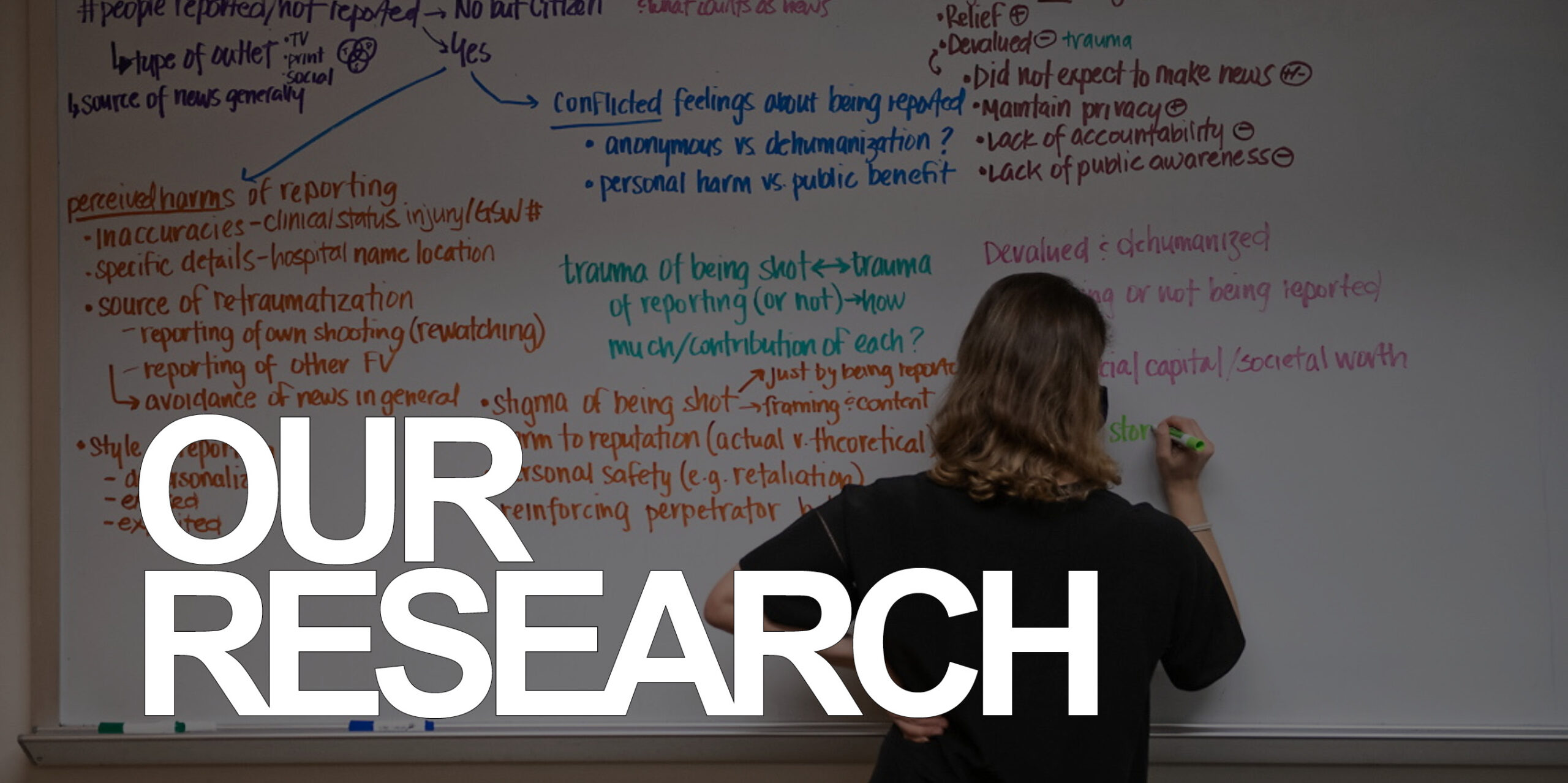

We're not just doing this research to park it in a journal. We're doing this research to inform how to make gun violence reporting better, how to make gun violence reporting the most ethical, empathetic, and impactful reporting possible so that we can prevent it.

- Dr. Jessica Beard

Dr. Beard, along with her interdisciplinary team of researchers, were interested in answering four questions. Click on the questions to explore the research.

Kelly McBride is the senior vice president of The Poynter Institute. She’s also the chair of the Craig Newmark Center for Ethics and Leadership. She’s seen the impact of our research first-hand.

We’ve done a lot over the past five years.

But there are four projects we’d like to highlight here:

1. The Toolkit & The Workshop

2. Survivor Connection

3. The Second Trauma

4. Association of Gun Violence Reporters

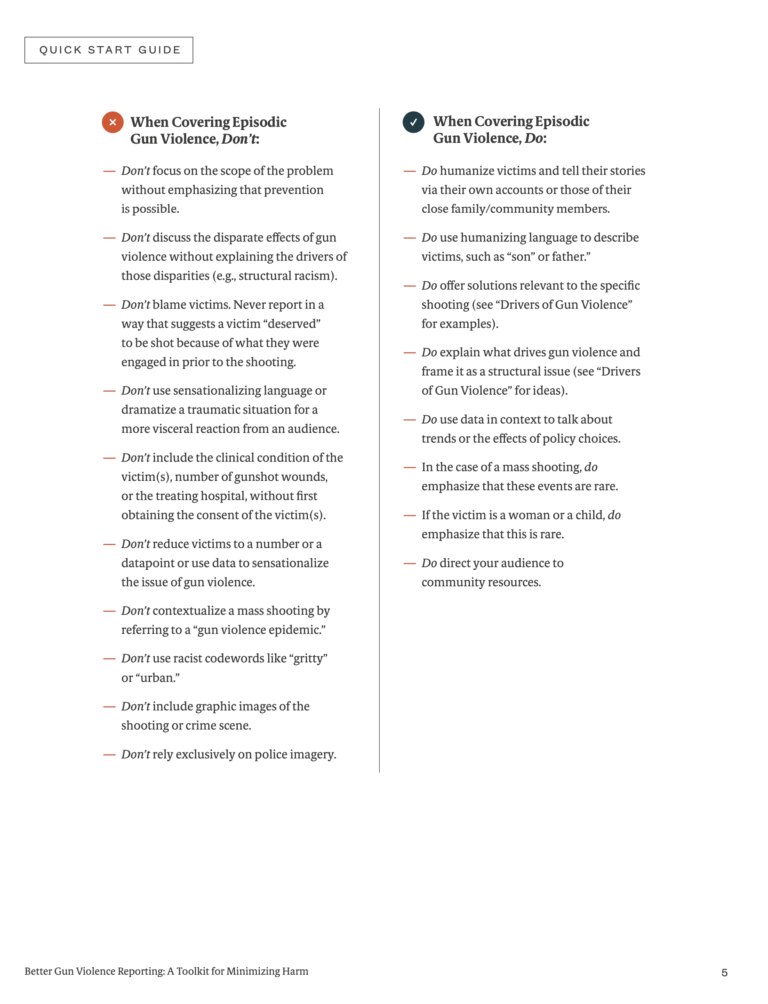

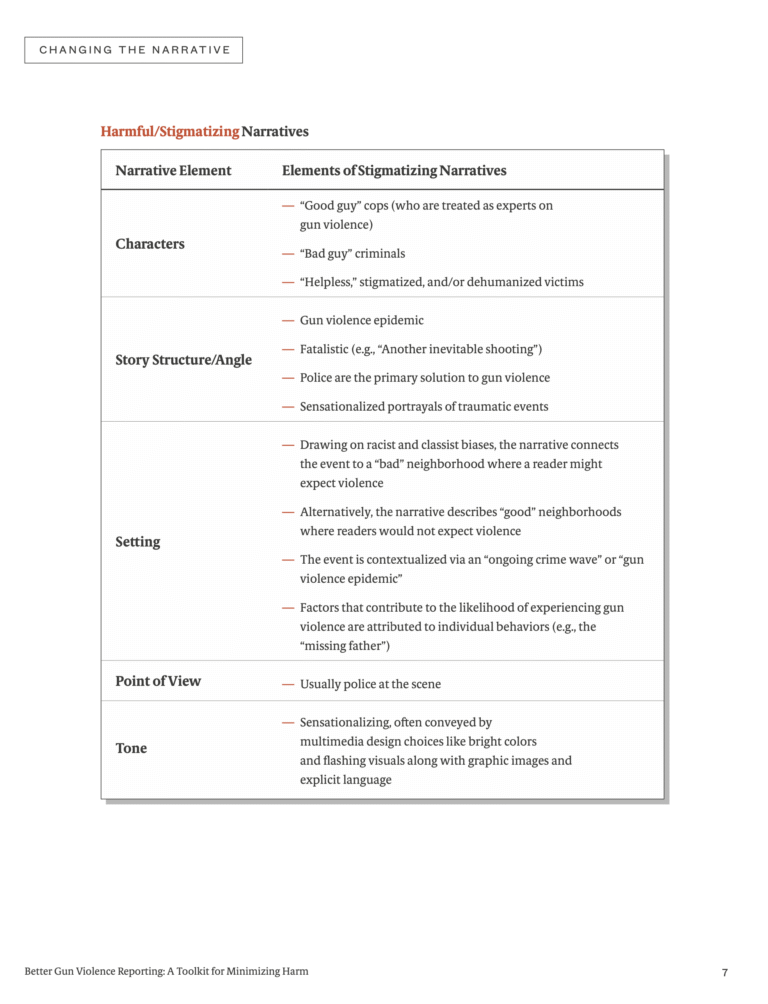

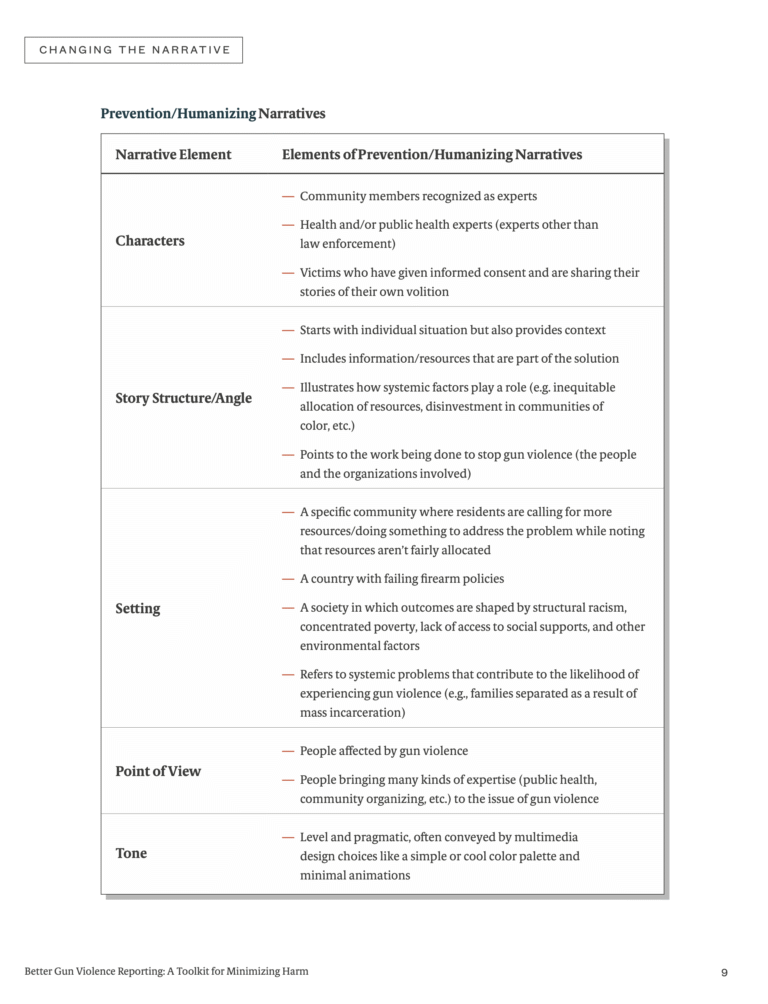

After several rounds of follow-up interviews with journalists, Better Gun Violence Reporting: A Toolkit for Minimizing Harm came to life. It was created in collaboration with FrameWorks Institute, with support from the Stoneleigh Foundation

By the end of 2024, more than 500 copies of the Toolkit had been handed out. Hundreds more have been downloaded from our website. And we’ve got plans for more Gun Violence Prevention Reporter Certification workshops to come.

PROJECT SPOTLIGHT

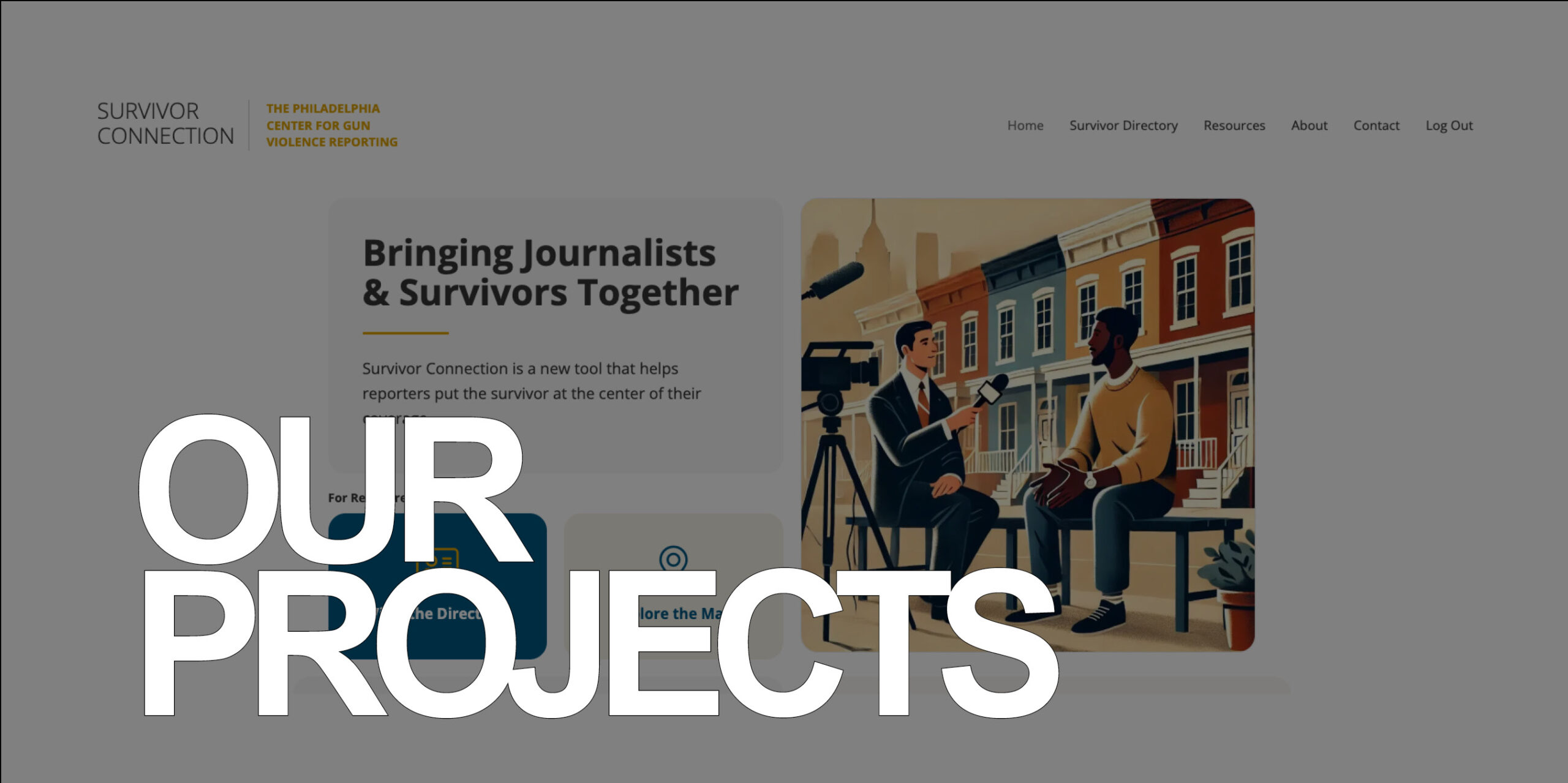

Survivor Connection

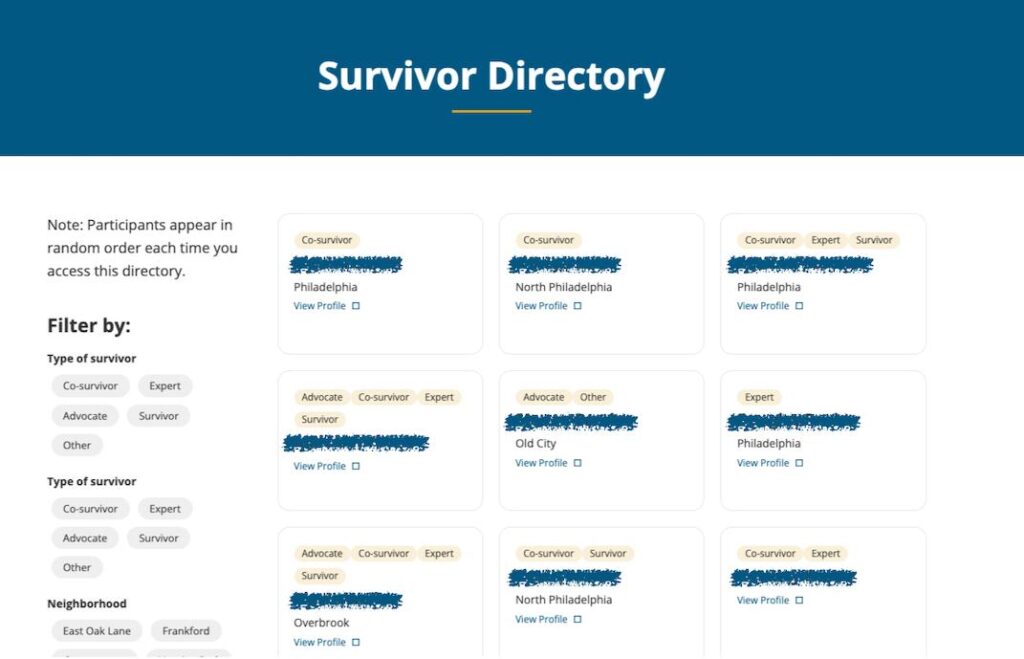

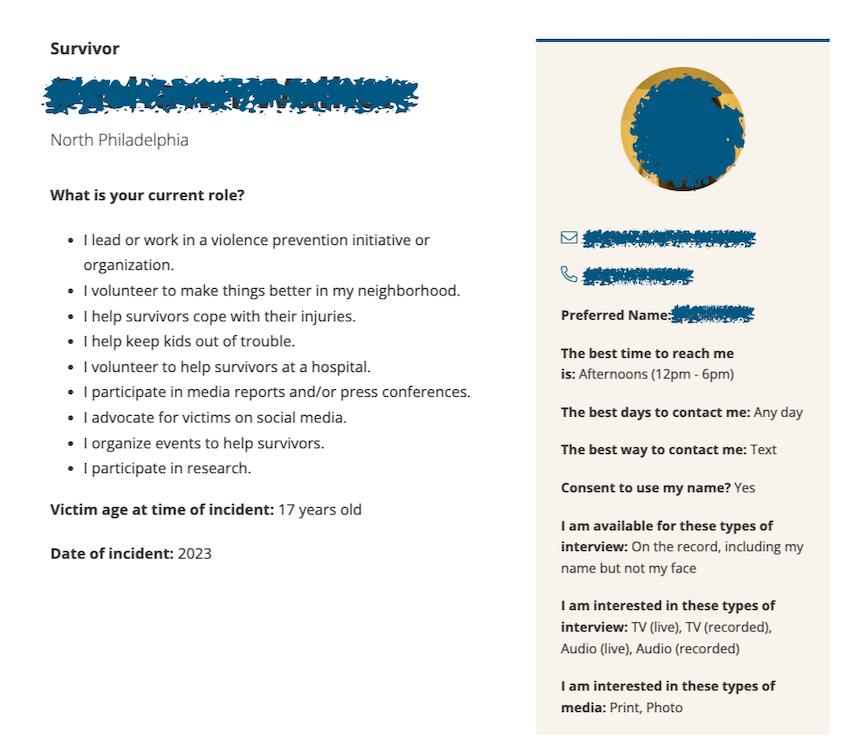

More than 17,000 people have been shot in Philadelphia over the last decade, but journalists often report difficulty finding lived-experience experts to include in their coverage — especially on deadline.

The result? Journalists often lean heavily on law enforcement narrators who rarely present the community perspective, tend to focus on reactive measures to gun violence, and often lack the expertise to speak about public health solutions to gun violence.

Another scenario (and this one can be particularly harmful): Journalists crowd around the bereaved family of the city’s latest (often atypical) gun violence victim, and begin asking questions they may not have the capacity to answer. This is often done without anyone there to support the family, without obtaining informed consent for the interview, and without addressing the preventative nature of gun violence.

Sometimes, family members learn about their loved one’s loss for the first time from reporters knocking at their door.

Survivor Connection has the potential to turn America’s gun violence narrative on its head.

How? By connecting journalists with a vast array of lived-experience experts who have already expressed an interest in speaking with them.

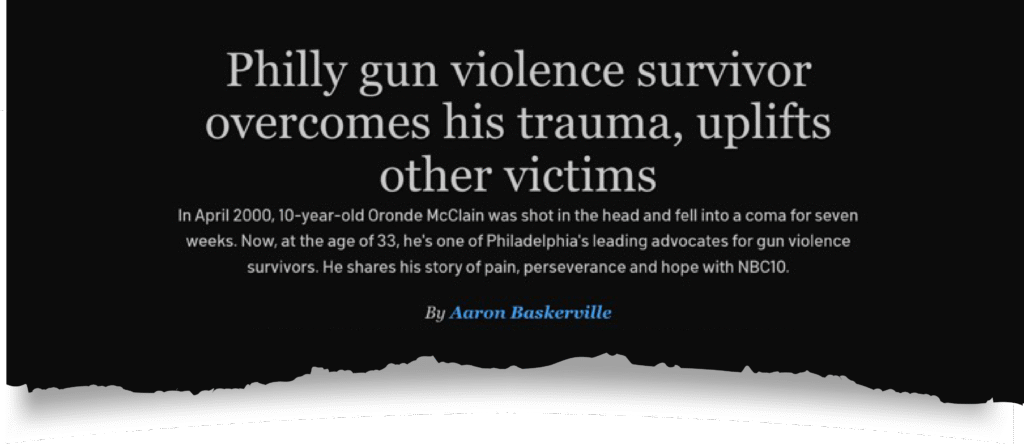

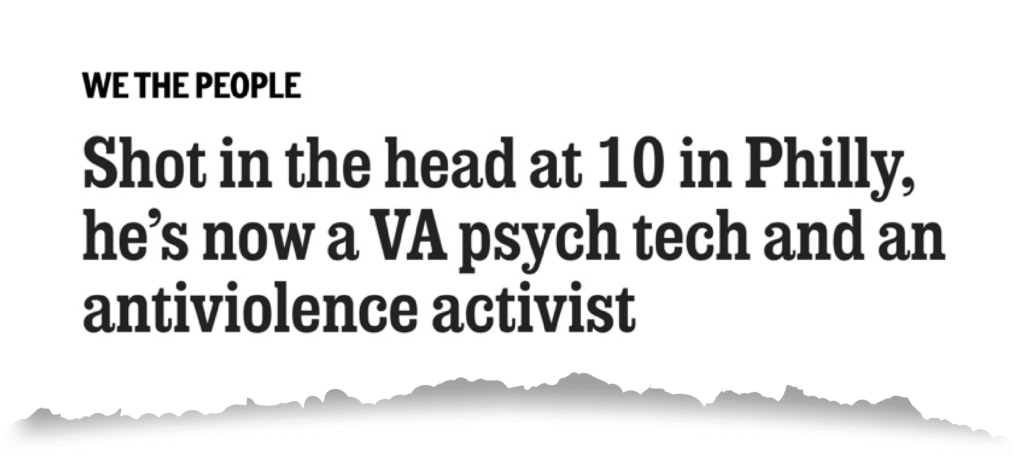

Here’s program director Oronde McClain.

By the time Survivor Connection launched in February 2025, 90 lived-experience experts, including those who had survived firearm injuries (we refer to them as survivors) and those who had lost loved ones to gun violence (we sometimes refer to them as co-victims), had already received training in media literacy, trauma, and public health solutions to gun violence. That number has since grown to more than 150. Hundreds more have expressed interest in participating.

The program is simple. After receiving their training, the lived-experience experts share various pieces of information that are then posted to a secure online portal. This includes their neighborhood, contact information, general availability for interviews, and some contextual information about their experiences.

Survivor Connection profiles are confidential, except to registered journalists.

Survivor Connection was produced with crucial support from the Stoneleigh Foundation, which funded a fellowship for Oronde to develop and facilitate the project.

Survivor Connection was produced with crucial support from the Stoneleigh Foundation, which funded a fellowship for Oronde to develop and facilitate the project.

PROJECT SPOTLIGHT

The Second Trauma

Ever notice how similar stories of gun violence are to each other?

Shots rang out at __ o’clock. Emergency crews rushed to ___ street, where they found a ___-year-old man suffering from ___ gunshot wounds.

Here’s a paramedic performing CPR.

Here’s the victim’s family member collapsing in tears.

Here are bullet casings being bagged as evidence

Here’s blood on the pavement.

Here’s police tape going up.

Here’s a vague description of the suspect.

Here’s surveillance video showing the shooting.

Here are scant details on a couple other shootings that happened in a different neighborhood.

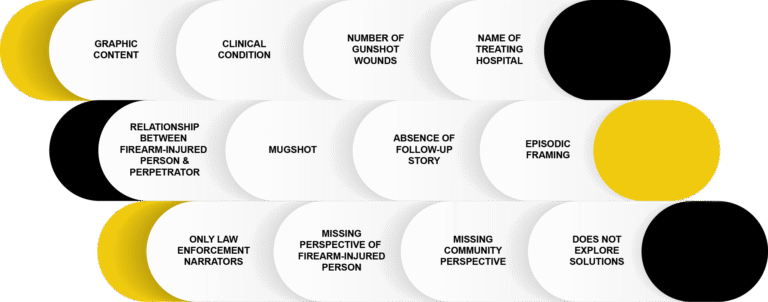

As we’ve learned from Dr. Beard’s research, episodic stories that focus on single shooting events or a cluster of events, without a discussion of the root causes of gun violence and proven solutions to gun violence, can be harmful to individuals, communities and society more broadly.

PCGVR wanted to create something for journalists that could help them understand this harm. In collaboration with the Logan Center for Urban Investigative Reporting at Temple University, we produced The Second Trauma.

The 25-minute documentary explores the impact of the media on various gun violence survivors and co-victims, including PCGVR team member and The Second Trauma producer Oronde McClain. It also offers solutions for journalists.

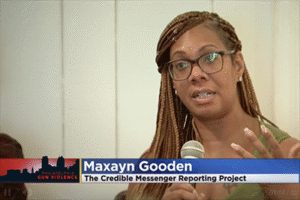

The Second Trauma was first screened at Temple University as part of PCGVR’s Credible Messenger Film Festival, which showcased various documentaries put together by survivors and co-victims, in collaboration with working journalists.

The documentary officially premiered at the Temple Performing Arts Center in Spring 2024. Several more screenings followed, each sparking thoughtful discussion between PCGVR and members of the media. More than 700 people have attended a screening to date.

Now, a bit more about the various impacts of traditional gun violence reporting. Here’s one: it can make communities less safe. Our Director of Operations, Eric Marsh, has some insight to share.

PROJECT SPOTLIGHT

Association of Gun Violence Reporters

If you’re a journalist, you may be thinking, It’s all well and good to tell us to do things differently, but you don’t know the realities of my job.

We developed a resource driven by people who do.

Implementing change isn’t always easy, even with the best intentions. We also recognize how harmful covering gun violence can be for journalists. The risk of psychological injury is real. But here’s something else we know: the power of the peer.

We were keen to develop a resource that is for journalists, by journalists — something reporters can lean on when they want to discuss an idea, are looking for a good public health source, or just need to vent.

The Association of Gun Violence Reporters, or AGVR, was launched in December 2024 by four gun violence reporters from across America — among them, Abené Clayton and Jennifer Mascia, featured earlier in this report.

And here’s the beauty of it: AGVR isn’t just for full-time gun violence reporters. It’s for any kind of reporter.

Whether you’re a Business reporter looking into the business of guns, a Health reporter interested in a public health approach to gun violence, or a General Assignment reporter assigned to the latest shooting, know this:

Virtually every journalist in America will cover gun violence at some point in their careers.

“This beat is not like other beats,” Jennifer says. “It can be a lot.”

“And we want to make sure that when people do it, they don’t walk away feeling like they’ve added to the problem,” says Abené.

Here’s Abené with more on what AGVR has to offer.

One of their early members? Alaina Bookman.

In addition to our own projects, we’ve helped other organizations on theirs.

The Poynter Institute has an excellent new course that helps American newsrooms transition from traditional, harmful crime reporting to reporting that can positively impact communities.

We’ve been honored to be included in Poynter’s curriculum, presenting the perspective of lived-experience gun violence experts to several cohorts of journalists from across the country.

Kelly McBride is the senior vice president of The Poynter Institute. She spoke earlier in the report about the impact of the lived-experience voices in our research. But important as those experiences are, the impact of bad gun violence reporting goes beyond the harm it causes to individual community members.

And the impact doesn’t stop there.

Some of our impact is very tangible — say, the number of community members we’ve supported (more than 300) or the number of people who have attended one of our documentary screenings (more than 600). And some of our impact is and perhaps always will be more difficult to illustrate — for example, the amount of trauma that is prevented when a journalist applies our training to their practice, or the number of shootings that don’t happen because community trauma has been reduced.

Let’s start with some tangibles.

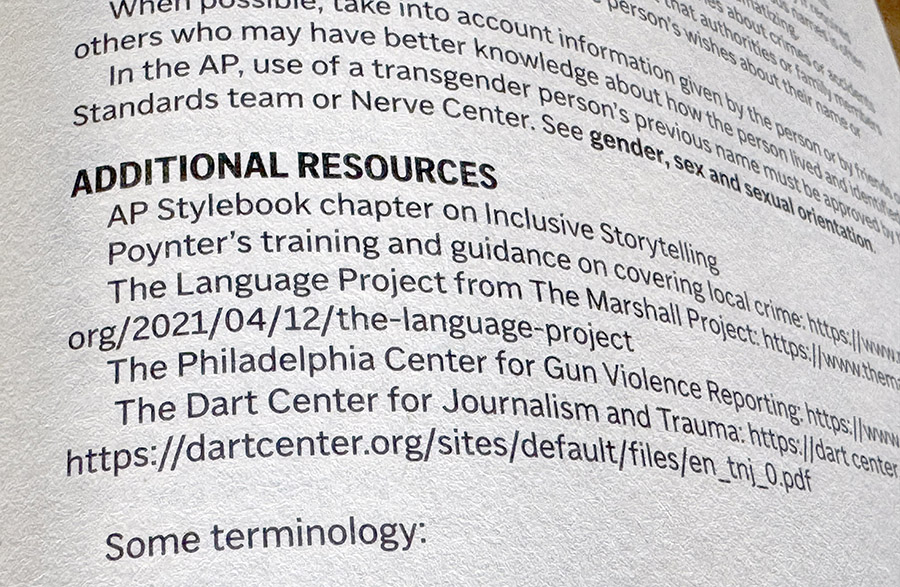

PCGVR was listed as a recommended resource in the latest edition of the Associated Press Stylebook.

In June 2024, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued a landmark Surgeon General’s Advisory, declaring firearm violence in America to be a public health crisis.

In doing so, he referred to the ripple of harm that cascades from gun violence, including to those “who constantly read and hear about firearm violence in the news.”

According to two people close to the Surgeon General, PCGVR’s work informed this advisory.

Our work was also included on the short list of recommended resources from the state of Pennsylvania’s Gun Violence Resiliency Needs Assessment, and is closely reflected in one of their recommendations: “Train journalists on trauma-informed reporting and interactions with violence-affected individuals.”

And our impact doesn’t stop there.

We met with deputy directors of the White House Office of Gun Violence Prevention.

We’ve consulted journalists across the country.

Visited dozens of newsrooms.

Supported training.

Presented keynotes.

Produced panels.

Bridged, influenced, informed, advised.

Watched the numbers, looked for the stories, amplified the voices, and produced nearly 250 editions of the Weekly Brief newsletter on gun violence prevention in Philadelphia (if you haven’t signed up for it yet, you can do so here!).

PCGVR’s work has impacted communities, academia, and the craft of journalism.

And it’s impacted us, too.

Here’s how we’ve felt that impact.

As we reflect on our first five years of impact, we are filled with gratitude.

Gratitude for every survivor and co-victim who shared their expertise and with it, their pain — in our research, our workshops, our panels, in virtually every tool we’ve created — with hopes of making someone else’s experience with the media healing instead of harmful, and to hopefully prevent more violence.

Gratitude for every journalist, every newsroom manager, every J-School instructor who has taken an interest in our work, attended one of our panels, our trainings, our screenings, or just perused our website for resources that can help them do this very important job, better.

Gratitude for our donors, without whom the impact we’ve had over the past five years would still be an idea, a dream, a frustration.

FOR THEIR FUNDING SUPPORT:

The Stoneleigh Foundation • Independence Public Media Foundation • Spring Point Partners • Knight Foundation • The William Penn Foundation • HFGF • Knight-Lenfest Local News Transformation Fund • The Lenfest Institute for Journalism • The Alfred and Mary Douty Foundation • Reynolds Journalism Institute at the University of Missouri • Philadelphia Office of Violence Prevention • The Barra Foundation Directors Grant Program

FOR THEIR SUPPORT IN KIND:

WHYY • Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists • Reynolds Journalism Institute at the University of Missouri • Mothers in Charge • AH Datalytics • Action Tank • The Scattergood Foundation • Resolve Philly • Fels Lab at the University of Pennsylvania

FOR THEIR PARTNERSHIP:

Columbia Journalism Review • Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma • The Guardian: Guns and Lies • Guns & America, WAMU • Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions • Kouvenda Media • Logan Center for Urban Investigative Reporting • Mothers in Charge • Need in Deed • Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists • Philadelphia Obituary Project • Revive Radio • Seeking Solutions: Gun Violence in Missouri • The Student Vanguard at Community College of Philadelphia • The Trace & Up the Block • YEAH Philly • Zero Homicides Now • WHYY & Billy Penn • WURD Radio • 5 Shorts Project

FOR THEIR RESEARCH PARTNERSHIP:

Christopher Morrison • Jennifer Midberry • Sara Jacoby • Iman Afif • Anita Wamakima • Evan Eschliman • Leah Roberts • Shannon Trombley • Tia Walker • Laura Partain • Siena Wanders • Tyrone Muns • Kallie Palm

Finally, thank you, dear reader, for exploring some of our impact thus far. We can’t wait to share all that is still to come.